Carpenter-mimic Leafcutter Bee, Megachile xylocopoides

I was contacted by Tracy L. Elfers who lives in Satellite Beach, Florida, about this wonderful Carpenter-mimic Leafcutter Bee, Megachile xylocopoides, which has built its nest cells in a mail box among the envelopes and letters! Tracy's emails were a delight to read, and I love to receive emails such as this!

Tracy has very kindly allowed me to share the video she recorded, as well as the photographs, on this page.

Watch: A Carpenter-mimic Leafcutter Bee In Action

Below is a video (supplied by Tracy) of the lovely Megachile xylocopoides carrying a segment of leaf back to the nest cells she is constructing between several pieces of paper. Not all leafcutter bees rely on hollow stems for building their nests!

You can see the bee arriving at her nest cells with her leaf segment, then carrying the leaf with her for constructing the nest cells. Then, job complete, finally, she climbs out and flies away. The whole process of depositing one leaf into her cell takes about 3 minutes.

|

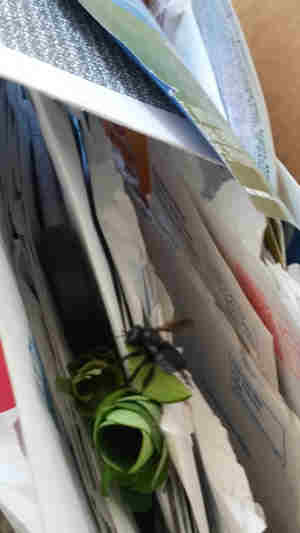

Here she is (right), a Megachile xylocopoides female, having arrived with a piece of leaf which she carries folded beneath her abdomen, to the stacks of envelopes where she is building her nest cells. Leafcutters can be very opportunistic about nest sites, whilst others are rather picky. |

|

|

Some Leafcutters will nest in empty snail shells, pine cones, folds in bags, or in packets of seeds, between rocks....all sorts! However, they may also use 'pre-constructed' tubes or tunnels in the form of hollow canes or similar. Some species may even nest in the abandoned 'burrows' of other bees. |

|

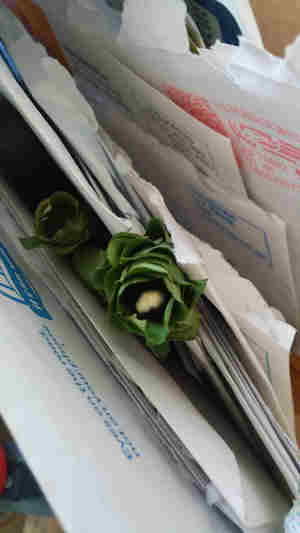

Leafcutters may use segments of leaf or petal for constructing the walls of cells, and even the whole of a cigar-shaped tube which houses them, like this one. |

|

|

Megachile xylocopoides may be seen foraging on Bidens, Bornchia, Cephalanthus, Itea, Helenium, Helianthus, Elephantopus, Rhus, Gaillardia, Mikania, Oxypolis, Phaseolus, Polygonum, Rubus, Rudbeckia, Senecio, Solidago, Trifolium, and Vernonia. Graenicher (1930) records xylocopoides on Poinsettia and Citrus. (Source: Mitchell, T.B. 1962 Bees of the Eastern United States. North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin No. 152) |

|

They can be found in Louisiana and Florida, and as far as Maryland. They are active from March to September, extending possibly until November in warm climates. |

|

|

As you can see, she takes the segment of leaf inside the entrance of the cigar shaped tube she has created. Note she has a beautiful black, shiny abdomen, and looks a little like some of the carpenter bee species (but her nesting habits are completely different). |

|

|

Here she is, now entering her "leaf-tube", carrying her leaf segment beneath her. |

|

As she enters the tube, you can see a creamy white little patch of pollen. This is because she is revealing the underside of her abdomen. She collects pollen on the underside of her abdomen, as seen in other leafcutter bee species. |

|

Here we see completed 'tubes' with the very end sealed up with a piece of leaf. Amazing little engineers, bees are! |

|

Other bee-haviours

I have limited access to information about this specific species, however, Tracy described to me certain behaviours that in one sense are quite similar to the carpenter bee of the Xylocopa genus.

In particular, Tracy found that it responded to human or animal movement.....

"If my local stray cat happens to be sitting at my feet (which is by her nest) she flies in crazy fast horizontal lines right above his head. He's swatted at her a couple of times and once she even dropped the leaf she was carrying then went after the cat. She's done the same thing to me. When I've moved out of her way, she follows me, flying in those same 6-8" horizontal quick movements...back and forth, back and forth".

My suggestion was that the bee senses vibrations near the nest, and is investigating to assess whether there is a threat and to discourage anyone from being around the nest. In my experience and that of others, male species of carpenter bees behave in a similar way, albeit male carpenter bees cannot sting, so any ‘flying at’ and ‘following’ is bravado, since he can’t sting anyone!

A dilemma!

One of

Tracy’s dilemmas was what to do about the cells. Wonderful as leafcutter bees are, it wasn’t

exactly convenient to have them build their egg cells in her mail box among her

mail!

However, soon the tubes of cells were all sealed up, and Tracy was (very carefully) able to extract necessary mail from her mail box!

There then followed other questions: would the bees be safe in the porch, or should she place them in the garage. Rodents can be a danger in the garage. In fact, relocating bees can be problematic, and I tend to recommend it only as a last resort. At the end of the day, can you be absolutely sure that where you’ll be putting them is better than where they are?

On the other hand, some people bring mason bees into the house during the winter months, and put them out again perhaps in late February depending on weather and location. Potentially, the same could be done with the leafcutter cells.

Around the porch were lizards of all types, from brown and green anole lizards, skinks, geckos, glass lizards, curly-tail lizards, racerunners and more. I have read that anole lizards are thought not to be dangerous around honey bee hives, and actually may help protect against wax moth.

Whether or not any of the lizards would eat leafcutter bee larvae, or whether they might potentially damage the cells whilst trying to get to some other predator insect of the bee larvae, would be an interesting question.

Tracy then had a great idea of placing a lid on the mail box with a hole, to offer at least some protection, but also some means of escape.

I am always touched to find there are so many people out there who do their absolute best to help bees. It’s wonderful, and I’m always heartened to learn of it!

Read more about Leafcutter bees.