The

Wool Carder Bee

Anthidium manicatum

Updated: 26th February 2021

The Wool Carder Bee, Anthidium manicatum is a lovely bee, and fascinating to observe, particularly as some of its behaviours are so distinctive.

Perhaps this should not surprise us - it is, after all a member of the Megachilidae family of bees, along with that other delightful group to watch - the leafcutters.

Looking Out For Wool Carder Bees - Anthidium manicatum

If you want to see these bees, one of the best places to catch them is around lamb's ear - (Stachys byzantina) where they may be foraging from May to August, depending when the lamb's ear is in bloom.

Later in this article is a short video of a female wool carder gathering plant hairs (a term known as 'carding'1) with which to create her nest cells.

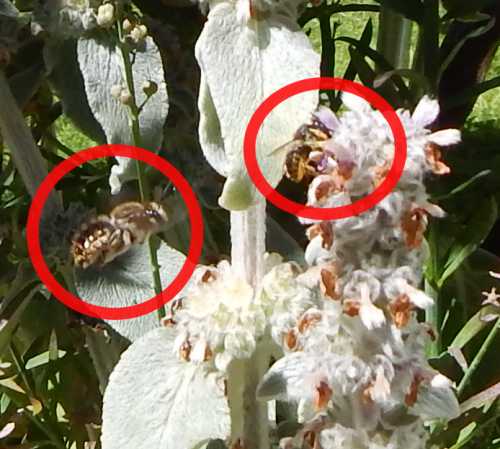

Wool Carder Bee, Anthidium manicatum on lamb's ear - Stachys byzantina.

Wool Carder Bee, Anthidium manicatum on lamb's ear - Stachys byzantina. Wool carder bees are beautiful bees - a delight to watch.

Wool carder bees are beautiful bees - a delight to watch. Look out for the lovely wool carder bee foraging on lamb's ear. Above - a male.

Look out for the lovely wool carder bee foraging on lamb's ear. Above - a male.Wool Carder Bee Nesting Habits

Lamb's ear is a firm favourite with wool carder bees particularly for constructing her nest cells.

The female gathers the hairy fibres (trichromes) from the plant into a ball, and takes it back to her chosen nest site.

Below is a video of a female gathering hairs from a lamb's ear plant:

Nests are made in existing cavities, usually hollow stems, dead wood or small holes and cavities in trees. At the nest, the female fashions the hairs into cells where she lays an egg, and leaves behind food (a 'mass' comprising pollen and nectar) to feed the emerging offspring2.

The female creates at least one, but usually multiple cells in a single cavity, which is finally plugged (called a 'terminal plug') with organic and inorganic matter that is carried to the nest2.

In the UK a single generation of offspring is raised each year3.

However, a study of Anthidium manicatum in New York state suggests that new bees either emerge later that summer as the second generation of a bivoltine (producing 2 broods per season) life cycle, or overwinter as prepupae and emerge the following spring (Payne et al 2010, citing Kurtak, 19732).

Research suggests that female bees prefer to initiate nests in sites located high above the ground, which are also less likely to contain spider webs, suggesting an adaptive explanation for nest site height preferences2.

Variations in appearance

Wool carder bee - Anthidium manicatum female foraging on lamb's ear - Stachys byzantina.

Wool carder bee - Anthidium manicatum female foraging on lamb's ear - Stachys byzantina.There are some variations in the strength and colouring of the yellow markings. At first glance, some specimens of Anthidium manicatum, could easily be mistaken for a wasp – see the striking yellow and black markings on the female above.

Mating And Mate Selection In Wool Carder Bees

Males defend floral territories visited by females that are foraging for food and nesting materials.

One of my patches of lamb's ear being patrolled by a wool carder bee male.

One of my patches of lamb's ear being patrolled by a wool carder bee male.

In my own garden, I have observed how male wool carders are very territorial and protective of their patches of lamb's ear, only allowing female wool carder bees anywhere near the flowers.

I have witnessed them not only chasing off rival males, but also bees of different species, literally dive bombing much larger bumble bees, seeing off mason bees, and any fly landing on a flower.

Wool carder bee male, patrolling a patch of lamb's ear.

Wool carder bee male, patrolling a patch of lamb's ear.What the males are waiting for, is an opportunity to mate with the females, who are 'flown at' or 'ambushed', pounced on, quickly mated with, and then left to continue foraging.

I managed to take some pictures, but it all happened so fast, that I'm afraid they are blurred.

On the left, a male wool carder bee approaching a female as she forages on lamb's ear flowers. He will pounce on the female. Mating is all over very quickly, and the female will continue with her foraging.

On the left, a male wool carder bee approaching a female as she forages on lamb's ear flowers. He will pounce on the female. Mating is all over very quickly, and the female will continue with her foraging.Still, you get a sense of the speed at which this all happens.

What is also clear from these photographs is that the males are larger than the females. In fact, some males can be particularly large, and research has shown that male size correlates with mating success2.

This male biased sexual size dimorphism is relatively unusual in the world of solitary bees, where females are usually larger than males3.

Bees may be larger in areas with significant abundance of flowers favoured by wool carders, suggesting a link between nutrition and size2.

Spikey Abdomens

An interesting physical characteristic of the males is that they have 5 visible spikes at the end of the abdomens.

Try as I might, I could not get a very good photograph of this characteristic, but you can just see 3 of them peeping out of the end of this male's abdomen if you look carefully. I highlight these in the lower photograph below.

According to Falk, these spines can be used to help the bee aggressively crush an intruder if needed!

I have never observed this behaviour, but I have certainly seen them 'head butting' other insects!

Foraging Habits Of Wool Carder Bees - Attracting Wool Carder Bees To Your Garden

Female wool carder bee.

Female wool carder bee.I have to say that I made a deliberate effort to attract wool carder bees to my garden.

One of the patches of lamb's ear in my garden - a sunny spot beneath the plum tree.

One of the patches of lamb's ear in my garden - a sunny spot beneath the plum tree.In making the effort, I planted lamb's ear - I already had at least two other favourite plants: purple toadflax and hedge woundwort.

This patch of lamb's ear is in my front garden.

This patch of lamb's ear is in my front garden.As the patch grew, I transferred young plants to two other areas, one in the front of the garden, and an additional spot in the back. This means I now have 3 patches of lamb's ear, along with the other plants these bees like to forage on.

My reasoning is that these three parts of my garden vary in the amount of sun they get during the day, and I believe this slightly affects the blooming of the plants. I also felt it would be interesting to see whether a particular patch was preferred over another.

What I found was that all of the patches of lamb's ear were foraged on by females and patrolled by males.

The female wool carder also took a liking to the purple toadflax, and the hedge woundwort behind my greenhouse.

In my efforts to increase forage and populations of bees, I also gave lamb's ear and purple toadflax plants to a neighbour just around the corner, and some to a concerned friend in the next village.

I recommend that if you are in the same position with bee-friendly plants to spare, find out if you can give them away to a neighbour, school or gardening group - where they will be used.

In addition to lamb's ear, purple toadflax and hedge woundwort, wool carder bees may be seen visiting black horehound. They apparently also gather plant hairs from great mullein and yarrow.

References

1. Graham KK, Brown S, Clarke S, Röse USR, Starks PT. The European wool-carder bee (Anthidium manicatum) eavesdrops on plant volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during trichome collection. Behav Processes. 2017 Nov;144:5-12. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2017.08.005. Epub 2017 Aug 19. PMID: 28830833.

2. Payne, A., Schildroth, D.A. & Starks, P.T. Nest site selection in the European wool-carder bee, Anthidium manicatum, with methods for an emerging model species. Apidologie 42, 181–191 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2010050.

3. Field Guide to Bees Of Great Britain And Ireland by Steven Falk.

If you found this page helpful or interesting, I'd really be grateful if you would share it with others - if not this page, perhaps another, such as Gardening For Bees.

Thank you so much :) .