Ethical Dilemma: Is It Okay To Kill Bees In Order To Test Insecticides?

Written: 2019. Updated: 28th February 2021

During the

process of testing insecticides on bees, some may die. Is it okay to test insecticides on bees?

Elsewhere on this website, I refer many times to the testing of insecticides on bees. Bees are one of the species specified by regulatory bodies across the world upon which insecticides must be tested.

However, I point out elsewhere on this website that regulatory tests are flawed, and in many areas, they fail to take account of impacts on wild species. Wild species may be significantly more vulnerable to the negative impacts of insecticides than honey bees, upon which regulatory tests have long relied.

I also

advocate that better regulatory tests are needed, and the agrochemicals

industry must be forced to comply with them PRIOR to authorizations being

granted.

Poor regulatory tests can result in more wildlife casualties than would otherwise have been the case had adequate testing been in place.

For example, the whole scandal of

neonicotinoids meant that independent scientists needed to provide yet more and

more evidence to counter the flawed studies allowed by agro-chemical industry-friendly

regulators, thereby necessitating the need for further tests.

As a result, yet more bees

were needed for the testing of these poisons, and inevitably, more bees died as a result of neonicotinoids in the environment.

Had regulatory tests been adequate in the first place, mass bee deaths and colony losses could have been avoided, and the additional research would not have been required.

All of this brings me to the issue of the ethics of regulatory testing, given that species die in the process of tests being conducted.

This issue has long been on my mind, such that I had considered writing a page about it years ago. Then recently I was asked the question directly:

“Do you agree with the testing of insecticides on bees? After all, bees are killed in the process”.

So what is my personal position on all of this?

The fact is, I feel genuinely uneasy about these tests overall, and always have, even whilst advocating that at the very least, tests should be fit for purpose. This is because I find even the thought of bees being willfully killed, very upsetting.

Does it serve a greater good to kill bees for regulatory tests?

Arguably, a

greater good is served by conducting these tests – or should be!

However, the EU and EPA failure to regulate properly in

the case of neonicotinoids has unfortunately meant that the greater good was not served - and this continues to be the case - including in the EU where Sulfoxaflor and other next generation neonics have been approved, despite a supposed 'ban'. As a result, bees suffer thanks to these toxic chemicals, and more poison is allowed into the eco-system than would have been the case had the regulatory tests been adequate.

In short, regulatory tests can only claim to serve 'the greater good’ if they are adequate in the first place, since the aim should be to minimise deaths and damage to wildlife, not hide it as a way to appease the public for the sake of manufacturer profits!

Thus,

regulatory tests from the EU and the EPA, have failed at the first hurdle.

But what if

regulatory tests really were effective?

Would it be okay then?

Below, I suggest an alternative approach to crop protection.

However, in answer to the question above, I suspect that if tests really were effective, hardly any insecticides – if any at all – would be authorized

for use, especially over large areas of land.

Necessity is the mother of inventions, so I believe this would quickly necessitate the need for growth in other areas of crop protection, which could then move through the regulatory system with relative ease.

For example, some farmers are already using wasps for pest control. Natural alternatives also exist, such as the use of garlic solution for controlling molluscs (which has scientific backing for its efficacy - see my page about its use on Lupins).

Ultimately, I think if high hurdles were set for chemical insecticides, this would significantly reduce the number of harmful insecticides being produced and tested, because it would create pressure to develop alternatives. Manufacturers would get the message that spending millions of dollars on developing poisons which had an unlikely chance of being authorized, was a costly waste of money.

This indeed happened many, many years ago, when human pharmaceuticals had to be regulated to protect people from being sold poisonous quack medicines.

However, just one word of

caution here: regulations are still needed even for biological controls! For example, commercially reared bumble bees

have been found to potentially put wild species at risk. Wild species need to be protected from such

scenarios.

A future with an effective regulatory system?

In a system of proper regulation, other methods of agriculture might also develop and flourish, such as mixed

cropping, and using organic nutrition to create strong plants which can better

resist attack from pests and diseases.

A greater awareness and understanding of pest attack and impact might also spread among farmers.

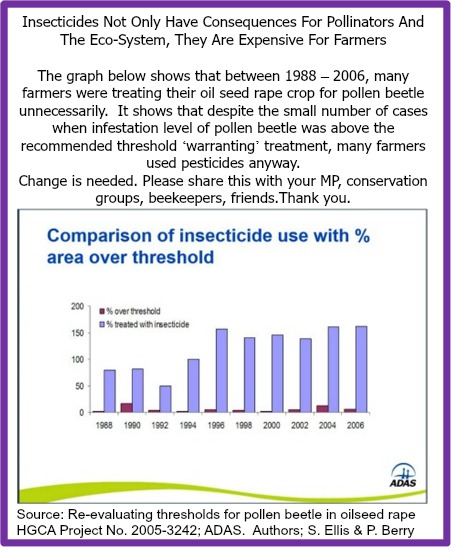

For example, if pollen beetle is spotted on oil seed rape, farmers might be tempted to spray crops immediately (and unnecessarily). A study by ADAS confirmed that crops were sprayed when in the majority of cases, infestation levels were so low that treating the crops had been unjustified, since crops can and do recover from pests if infestation is below certain levels.

I propose the focus of research and crop protection needs to switch to making plants naturally even healthier, or explore eco-friendly alternatives to repel 'pest' insects.