Scientist: Dr Charles Henry Turner, A Profile

Most people have heard of Charles Darwin and Karl von Frisch, but in the world of entomology and related subjects, there are many names barely heard of, despite their pioneering contributions to our understanding of invertebrates, including bees.

It seems, not everyone gets the acknowledgment they deserve whilst alive, and many don't even get it when they die!

And so, I have decided to begin sharing the contributions of those people - a kind of posthumous tribute to the scarcely remembered heroes and heroines of the 'bee and entomology' world

But who should I start with in this new 'Profiles' section of my site?

Well, as I write, it will soon be 'Black History Month'*, and so I thought it would be fitting to start with the very significant contribution of an African-American scientist and zoologist, and to outline his work in entomology and animal behaviour. His name: Dr Charles Henry Turner.

*Black History Month:

February in USA & Canada

October in UK & Ireland.

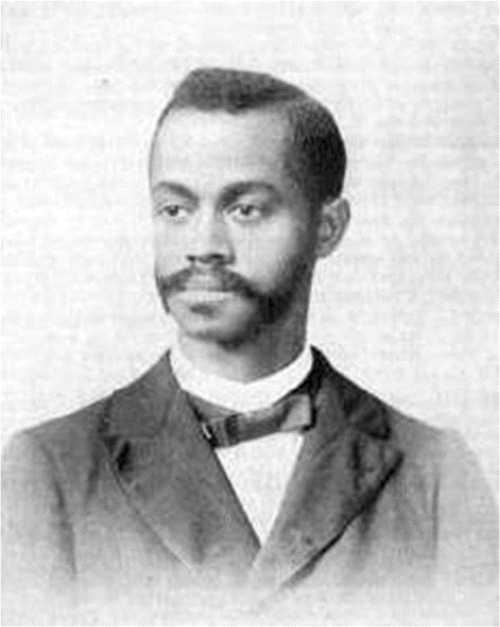

Dr Charles Henry Turner - Profile

Charles Henry Turner

Charles Henry Turner- Charles Henry Turner: born in 1867 in Cincinnati, Ohio, 2 years after the end of slavery in the US.

- Turner studied biology at the University of Cincinnati, gaining a B.S. degree in 1892. He was the first African American to receive a graduate degree from this particular University.

- In 1907, Turner earned a PhD in Zoology from the University of Chicago in 1907, quite possibly the first African American receiving a PhD degree from this institution.

- Turner had a wife and two sons, one named Darwin Romanes Turner, (after Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and George Romanes (1848–1894)).

- Turner was unsuccessful in gaining an academic post at a University, but became a teacher in a high school for African Americans in 1908, where he remained until he retired in 1922.

- Turner died of myocarditis in 1923, at the age of 56.

His death certificate incorrectly stated that his occupation was “druggist,” (i.e. pharmacist).

- (Sources: Giurfa et al (2021)1, Galpayage & Chittka (2020)2)

Key Achievements

- Aside from his degree and PhD, Turner published 71 papers on animal behaviour, including insect hymenopterans (particularly bees, wasps and ants).

- Turner pioneered concepts in insect navigation, learning, and memory.

His experiments were conducted in limiting circumstances, having no access to University laboratory resources or libraries, and without a team of assistant undergraduate/graduate students.

Galpayage & Chittka (2020)2 note that Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and George Romanes (1848–1894) were "famously generous in attributing intelligent behavior and mental abilities to animals, but their musings were largely based on observation and inference".

Galpayage & Chittka also make the point that later, scientists "largely rejected notions of advanced animal intelligence or insight".

However, Turner took the concepts seriously, and set out to prove his ideas via his own experiments.

"Enter Charles H. Turner, who took seriously Darwin’s assertion of the importance of individual variation as well as the idea that humans were not the only intelligent animal species. But Turner backed up this possibility with a rigorous experimental approach."

- Galpayage & Chittka (2020)

Sadly, his work remained off the radar, even when later scientists have explored the same concepts, in effect, "reinventing the wheels", years later1.

Dr Charles Henry Turner's Research On Bees

Of course, Turner studied other insects too as well as many animals and birds, all of which are beyond the scope of this article, but here is an outline of some of his work on bees.

The nuptial dancing flight of long-horned bees

Turner was the first to describe the nuptial flight of long-horned bees, (solitary Melissodes bee species).

Turner observed that males chased females in complex mating flight manoeuvres. The males either grasped the females in flight or at the ground level, and rolled with them repeated times. He described this behaviour as a “nuptial ambuscade since it is a device, which promotes sexual union.”

Associative learning and visual memory in long horned bees

Turner performed field experiments recording activity around nest burrows, in particular, displacing 'landmarks' around nest entrances, and creating 'dummy' nest burrows.

With this experiment, Turner showed that bees learned the location of their nest entrances relative to surrounding landmarks that, when displaced, caused the bees to search in the wrong location.

Turner’s results thus demonstrated that bees learn to associate the nest with specific visual cues in the environment, which is then memorized so that they might draw on this information when returning to the nest location.

Turner concluded that, “By a process of elimination, the most consistent explanation of the above behavior is the assumption that burrowing bees utilize memory in finding the way home, and that they examine carefully the neighborhood of the nest for the purpose of forming pictures of the topographical environment of the burrow.”

Studies of stelid bees

Turner showed that these parasitic bees use multiple strategies, such as landmarks in addition to sunlight orientation.

Color vision in honey bees

Austrian physiologist and Nobel-Prize winner, Karl von Frisch, is widely credited with demonstrating color vision in honey bees, and published a paper on his findings in 1914, yet Turner had devised experiments investigating this phenomena 4 years earlier.

Unfortunately, Turner's experiments had some flaws (for example, no control group, and use of red cones to simulate flowers - whereas it was later shown that bees cannot see red).

However, Turner's experiments did at least show that bees were attracted initially to visual cues presented by flowers, but then rejected the flowers in the absence of honey reward, thus suggesting bees use both visual and olfactory cues in their approach to flowers.

Turner's work was therefore different from the work of von Frisch, which demonstrated that bees learned to associate different color cardboards with the presence or lack of a reward of sucrose solution, thereby illustrating that bees could see the cardboards as colored surfaces, with the exception of red, which bees tended to confuse with black.

In Tribute To Charles Henry Turner

In recent years, efforts have been made to raise the profile of Turner, such that Chittka refers to the work of Turner in his book, The Mind Of A Bee.

It is a sobering thought to consider that had Turner's work received the recognition it deserved, our understanding of the inner lives of bees and other animals, would have advanced sooner.

References

- Giurfa, M., Giurfa de Brito, A., Giurfa de Brito, T. et al. Charles Henry Turner and the cognitive behavior of bees. Apidologie 52, 684–695 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-021-00855-9

- Galpayage Dona HS, Chittka L. Charles H. Turner, pioneer in animal cognition. Science. 2020 Oct 30;370(6516):530-531. doi: 10.1126/science.abd8754. PMID: 33122372.

If you found this page helpful or interesting, I'd really be grateful if you would share it with others - if not this page, perhaps another, such as Gardening For Bees.

Thank you so much :) .