Why Do Bees Need Nectar And Pollen?

Updated: November 2023

It’s well known that bees gather nectar and pollen from flowers, but why do they need them - what are the specific benefits to bees?

Why bees need nectar and pollen and how they use it

First, a few quick points to note about bees, nectar and pollen:

- Nectar provides an important energy source (carbohydrate) –

it supplies a complex range of sugars.

- Honey derives its sweetness from nectar, which honey bees gather to make honey.

- Pollen provides bees with vital protein and fats which are crucial for developing young and adult bee health.

- Although all bees need pollen at some stage in their lives, not all bees gather it.

- Male bees do not collect pollen, and have no pollen baskets (corbicula) with which to transport it from flowers to the nest or hive.

- Cuckoo bumble bees do not gather pollen, and have no pollen baskets. However, pollen is required for rearing offspring, and so the cuckoo female relies on the host bumble bee species to

supply her offspring's needs.

- In a similar fashion, the cleptoparasite nomad bees deposit eggs in nests of solitary species, especially mining bees (Andrena). Nomad bees do not collect food for their offspring. Once eggs hatch, the larvae consumes the food stores intended for the offspring of the host.

Only females of bee species carry pollen conspicuously on specially adapted hairs on their hind legs or abdomens - but not if they are cuckoo species or cleptoparasites.

Only females of bee species carry pollen conspicuously on specially adapted hairs on their hind legs or abdomens - but not if they are cuckoo species or cleptoparasites.

The role of nectar and pollen in bumble bee and solitary bee colony development

Bumble bees

Queen

bumble bees seek nectar when they emerge

early in the year. Usually it will still be cold, and the

bumble bee queen

will need nectar in order to boost her energy resources very quickly.

She will also forage for quality pollen from pussy willows, winter

flower shrubs and other beneficial plants.

Queen bumble bees will have been impregnated the previous year, and will hibernate whilst fertile.

Once she has found a suitable nest site, she can then gather provisions ready for developing larvae, and then lay her eggs.

The provision she has made for the developing larvae, will contain vital protein in the form of pollen.

According to at least one study, it is believed the ovaries of bumble bees that have no access to pollen do not develop, and the fat bodies of these bees are relatively small3.

However, this is potentially disputed by other study which found no indication that pollen, (rather than nectar) foragers had more developed ovaries4.

Whilst incubating her eggs, the bumble bee queen will need to maintain her own energy reserves. In order to do this, she will have provisioned herself with a small pot of nectar from which she will feed herself.

Bumble bee worker foraging on white bryony.

Bumble bee worker foraging on white bryony.As the young bumble bees hatch, they will continue to feed until they are ready to assist in the nest.

When they are ready, the females will venture out of the nest as workers, and will gather more nectar for feeding the adult bumble bees, and pollen for the rearing of the

next bumble bee brood.

Solitary bees

Solitary bees also

provision each separate egg cell essentially with a pollen mixture, that

the developing larvae will consume as they grow.

However, once the female solitary bee has performed this task, she will have no further involvement in rearing the next generation of solitary bees.

Coastal leafcutter bee foraging on common restharrow.

Coastal leafcutter bee foraging on common restharrow.

The importance of nectar and pollen for honey bees

Nectar

Honey bees

need nectar and pollen for much the same reason as bumble bees and solitary bees, although they treat it slightly differently.

The nectar that is gathered by honey bees is taken back to the nest or

bee hive where it is used to feed adult bees, but it is also passed from foraging worker bees to worker house bees, and then is deposited into hexagonal honeycomb cells.

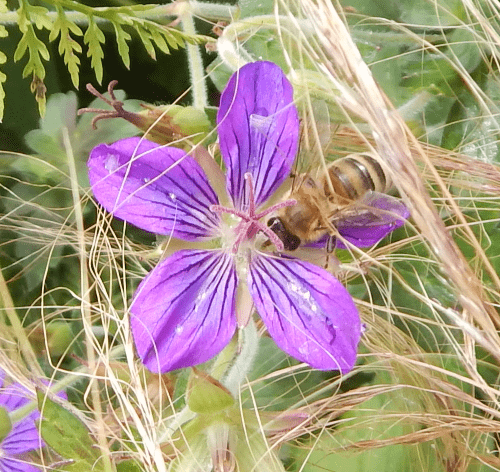

Honey bee foraging on geranium flower.

Honey bee foraging on geranium flower.After a process of fanning and evaporation,

the nectar will turn into honey, and will be capped over with wax by the

bees. Now that this nectar has been turned into honey, it will provide

a winter food source for the bees to dip into when they are unable to

forage outside for food.

You can read more about this, in

How Do Bees Make Honey.

Of course neither bumble bees nor solitary bees store nectar in this way (i.e. as a winter food store), since their

life cycles

are entirely different, and shorter than that of honey bees (although

the lifespan of individuals within colonies varies and can also be short

for honey bees – see

How Long Do Bees Live?).

Pollen

Flower pollen is taken back to the nest or

hive by foraging worker honey bees, where it is stored as bee bread. Along the way to becoming

bee bread, there are several changes to the flower pollen from the moment

it is gathered by an adult forager.

Firstly, the adult forager collects the pollen from the

anthers of the flower, and coats it with regurgitated nectar from the

honey stomach, in effect, gluing the pollen grains together to form a

compact pellet which is carried back to the hive or nest in the corbiculae

(pollen baskets on the rear legs).

These pellets are then compacted together inside the wax cells, with

additional honey, nectar and oral secretions1. The stored bee bread even helps to add a certain amount of structural integrity to the comb itself.

Pollen is also in effect, biosynthesized by

nurse bees into royal jelly, which is the main source of protein for

developing larvae and the queen (Ghosh et al 20202 citing

Winston, 1987, Paoli et al., 2014).

If honey bees cannot get enough pollen, this is harmful to the bees in several ways. You can read more about this on my page about how bees get protein and why they need it.

How do bees collect pollen?

This bee is carrying quite a lot of pollen on the 'scopa' of its hind legs.

This bee is carrying quite a lot of pollen on the 'scopa' of its hind legs.How bees collect pollen depends on the species.

Pollen is collected and carried by many bee species on hairs of the hind legs called 'scopa'.

On honey bee and bumble bees, the hairs on the hind legs as specially adapted to form pollen baskets known as 'corbiculae'.

You can read more detail about this subject on my page How Do Bees Collect Pollen?

Providing sources of nectar and pollen for bees

Wool carder bee on lamb's ear.

Wool carder bee on lamb's ear.It's not surprising that bees need good sources of nectar and pollen throughout the year, to cope with the rearing of broods and development of colonies. For anyone planning a bee-garden, it's also worth remembering that different species are more active at certain times of the year than others.

Wildflowers are increasingly important due to major losses of natural wildflower landscape.

However, the tremendous choice of herbs, cottage garden plants, fruit, vegetable plants, trees and shrubs which can be grown even in small spaces, offer plenty of opportunity for people and their communities, to play their part in helping pollinators.

See these lists of plants for bees for more information.

References

1. Carroll MJ, Brown N, Goodall C, Downs AM, Sheenan TH, Anderson KE. Honey bees preferentially consume freshly-stored pollen [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2021 Mar 25;16(3):e0249458]. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175933. Published 2017 Apr 21. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0175933

2. Ghosh, S., Jeon, H. & Jung, C. Foraging behaviour and preference of pollen sources by honey bee (Apis mellifera) relative to protein contents. j ecology environ 44, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41610-020-0149-9.

3. Duchateau, M.J. and Velthuis, H.H.W. (1989), Ovarian development and egg laying in workers of Bombus terrestris. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 51: 199-213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.1989.tb01231.x.

4. Simons MA, Smith AR. Ovary activation does not correlate with pollen and nectar foraging specialization in the bumblebee Bombus impatiens. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4415. Published 2018 Feb 20. doi:10.7717/peerj.4415